Decision R0012/2024 (R0012/2024-4 SHAPE OF A TETRA BRIK (3D)) of the EUIPO Boards of Appeal considered one of Tetra Laval’s well-known packages for liquids and particularly what “obtaining a technical result” means in the context of the shape of a trade mark.

Article 7 of the EU Trade Mark Regulation (EUTMR) states absolute grounds for refusal of registration of a trade mark including that a sign shall not be registered when the sign consists “exclusively of […] the shape, or another characteristic, of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result” (EUTMR, Art. 7, (1)(e)(ii) EUTMR)

Background

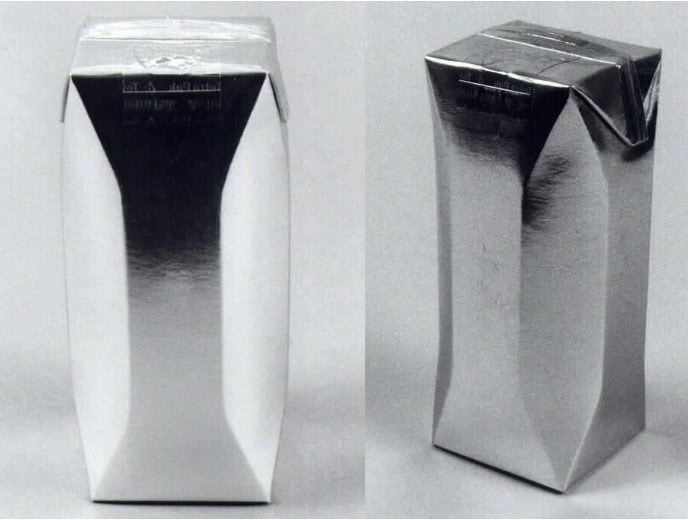

Tetra Laval applied in 2000 to register the shape shown in the picture as an EU trade mark (EUTM) in class 16 for “Packaging containers and packaging material made of paper or made of paper coated with plastic material”, and this was registered in 2004.

In 2022, Lami Packaging filed a request for a declaration of invalidity of the trade mark on two grounds: technical functionality (Article 7(1)(e)(ii) EUTMR), and the application being made in bad faith (Article 59(1)(b) EUTMR).

This had the result that the Cancellation Division declared the EUTM invalid as being exclusively a technical shape. As the registration was cancelled on the basis of Article 7(1)(e)(ii) EUTMR, the point regarding the trade mark being filed in bad faith was not considered.

However the Board of Appeal (BoA) reversed the earlier decision and found that the EUTM at issue was neither exclusively a technical shape nor had it been filed in bad faith – and this is Decision R0012/2024, which is the focus of this article.

Technical Functionality

In considering whether the features of the shape mark were technical and therefore excluded from registration under Article 7(1)(e)(ii), the BoA followed Lego as to how the assessment should be conducted: first, by identifying the essential characteristics of the shape in question; and secondly, by determining whether they perform a technical function.

Accordingly, in paragraph 32 of Decision R12/2024-4 the BoA identified 4 essential characteristics of Tetra Laval’s shape mark:

- A brick with four wall panels and four truncated angles creating an octagonal shape with a roughly square cross-section;

- The four truncated angles in the form of rounded hexagons/parallelograms, with a surface that is concave rather than plane;

- The four wall panels narrowing in their middle part and flaring upwards and downwards;

- The upper part of the brick equipped with a sealing fin crossing the top surface and extending to two corner flaps which are folded down to two of the vertical wall panels.

In addition, Tetra Laval’s International (PCT) patent application WO1997034809 was also considered because it also disclosed these features in a technical context.

The BoA concluded that the characteristics of the shape mark listed above

“allow increasing the capacity/used material ratio, while ensuring package stability and handling properties”.

Decision R12/2024-4, paragraph 44

However, while

“the contested mark was designed to achieve a certain result that is technical in nature, […] [t]his does not […] mean that all results of a technical nature are ‘technical results’”.

Decision R12/2024-4, paragraphs 49 and 50

This is in line with existing case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU),

“the expression ‘necessary to obtain a technical result’ must be interpreted as meaning that the essential characteristics of the shape must ‘perform a technical function’ in order to achieve a certain technical result’”.

Decision R12/2024-4, paragraph 51

Therefore, what is germane here is how “professional intermediaries of the foodstuff industry”, i.e. the users/buyers of the trademarked goods perceive the product with the trade marked shape to function (cf Decision R12/2024-4, para. 54). Importantly this contrasts with the method of manufacture of the trade-marked product (as considered in Nestlé).

Thus the BoA held that

“the technical result achieved by the first three characteristics […] merely relates to the manufacturing process of the product itself without influencing the function performed by this product.”

Decision R12/2024-4, paragraph 59

In other words, the interpretation of the term ‘technical result’ flows from whether the shape has a direct effect on the use of the trade marked goods in question by the user/consumer and this is separate from manufacture of the trade marked goods.

This is in line with the case law of the Boards of Appeal, to which the Decision refers, stating:

“the ‘shape of a chocolate bar’ case, [in which] the Court of Justice was asked in substance whether the shape of the ‘Kit Kat’ bar was functional on account of the fact that its essential characteristics allowed for efficient de-moulding, packaging and distribution and, more generally, for the optimisation of the mass production of the goods.

The Court of Justice answered that the absolute ground of refusal or invalidity applies where the shape allows a product to achieve a desired technical result when this product is in use, but it does not apply to the manner in which the goods are manufactured (16/09/2015, C-215/14, Nestlé KIT KAT, EU:C:2015:604, § 57).

Decision R12/2024-4, paragraph 52; our emphasis

Therefore Tetra Pak’s trade mark is not a purely technical shape because it

“is not the cause of a technical result impacting on the manner in which the product is used, but rather the consequence of industrial engineering on its design and production.

the fact that the contested mark allows for an efficient volume-to-surface ratio while preserving the stackability, storage and handling of the product does not concern a technical result within the meaning of Article 7(1)(e)(ii) [EUTMR]. Indeed, the ability of a shape to contain more liquids or foodstuffs or to be easily packed and grasped is not a technical result achieved by the product in the normal course of its use. The shape at issue does neither perform a function on its own, nor in relation to other products.

Decision R12/2024-4, paragraph 60–61

Thus only the technical features that contribute to the direct functionality of the container (i.e. to contain liquid [r.38] are those “that are performed by essential characteristics of shapes which consumers will be looking for in the products of competitors, given that they are intended to perform an identical or similar function” (Decision R12/2024-4, paragraph 42).

Therefore technical features of the trade mark relating to efficiency of manufacture or distribution are separate and different from any technical features of the trade mark that are recognised by the consumer. As the technical features that are unrecognised by the consumer also do not contribute to the function performed by the trademarked product the trade mark is not excluded from registration under Article 7(1)(e)(ii) EUTMR.

Bad faith

Turning to the submissions regarding bad faith, Lami Packaging alleged that Tetra Laval sought to protect the EUTM to artificially extend the term of its IP protection by substituting trade mark protection for patent protection.

Since the BoA found that Article 7(1)(e)(ii) was not applicable to the trade mark shape registered by Tetra Laval, the bad faith argument (under Article 59(1) EUTMR) was also rejected.

Conclusion

Will this affect registered design right? Technical constraints also bear here. Will these be paralleled?

Thus, again the Boards of Appeal have focused on the function of a trademark in allowing a consumer to distinguish between the origin of goods. Furthermore, the Boards of Appeal have affirmed that technical features that contribute to the consumer recognising the origin of goods are distinct from the technical features that contribute to commercial benefit of the proprietor of the trade mark. The implication is that the commercial benefits do not contribute to the recognition of the trade mark by the consumer and as these features, technical or otherwise, do not contribute to the consumer’s recognition of the origin of the trade-marked goods they do not fall within the ambit of Article 7(1)(e)(ii) EUTMR.

This decision was slightly different in that the alleged technical features that these proceedings were based on were previously published in a patent application of the proprietor. Thus this case highlights the difference between technical features of a trademark and technical features of an invention as defined in a patent application.

Finally, we also note how defining “features solely dictated by technical function” in this way might influence European Registered Design Right (EURDR).

EURDR is intended to protect the appearance of a protected product rather than its function. Thus it might be argued that the primary function of a EURDR is to define a product’s appearance, in parallel with the consideration of trademarks discussed above.

Therefore, technical features that contribute to the product’s appearance might be protectable under EURDR. Features relating to the designs appearance solely dictated by technical function are excluded from protection under EURDR. But following the trade mark Decision above, might there be two types of technical feature? First, technical features relating to the primary purpose of defining a product’s appearance, and secondly, features dictated by technical function but unrelated to appearance, e.g. features that contribute to efficiency of manufacture and/or distribution. Features in the first category are excluded from protection, but might technical features in the second, category protectable under EURDR?

Whether the reasoning in present decision R12/2024 could be applied to EURDR may depend on whether consumers of a trade mark are equivalent to an “informed user” considering a product with registered design protection. However, the distinction between technical features defined in a patent specification and the scope of technical features that do not prejudice trade mark registration might well be applied also to registered design protection.