NO END TO THE WAITING?

On 11th April 2013 the European Brüstle patent (EP 1040185) was revoked, but the EPO did so without considering morality issues; sadly, therefore, we are no closer to resolving the patentability of human stem cell inventions in Europe. As the EPO has not gone beyond the WARF decision (G 02/06) we will have to do so ourselves. We offer our own solutions and make a suggestion as to how EPO internal procedures may be modified for the future.

As background, Prof. Dr. Brüstle has parallel European and German patents relating to neural precursor cells, derivable from cells obtained from human embryos (as well as other sources). The patents are notable in that they were initially objected to in both jurisdictions as covering subject matter that necessarily required destruction of human embryos – thus rendering the claims unpatentable in accordance with the EPO’s WARF decision, as supplemented by the CJEU decision in C-34/10.

Brüstle German Federal Court Proceedings – Patent Maintained

In November of last year, the German patent was considered and the German Federal Court handed down its decision in Brüstle vs. Greenpeace (X ZR 58/07, the “German Brüstle decision”), holding Prof. Dr. Brüstle’s German patent valid in amended form, with a disclaimer to state explicitly that the method claimed does not encompass methods that destroy embryos. The decision was widely reported, but more should have been said about specific elements of the decision: namely

- i. the disclaimer was found allowable,

- sources of starting material that did not destroy embryos were accepted as being disclosed in the application as filed, and

- structures which were once embryos and whose development has been arrested so they can not complete the process of developing into a human being (but from which human embryonic stem cell lines can be derived) do not constitute embryos.

Brüstle EPO Opposition Proceedings – Patent Revoked

On 11th April 2013 oral proceedings were held in respect of the opposition against the Brüstle European patent, EP 1040185, and a decision was handed down on the day (the “EPO Brüstle decision”) though at the time of completing this article the EPO Brüstle decision has not yet been issued in written form. The key topic for parties to the opposition was application of the morality provisions of the European Patent Convention. Third party observations were filed on that issue. The stem cell patent world watched and waited for a final resolution of the stem cell patenting issue.

This resolution did not arrive, however, as the EPO instead promptly revoked the patent for added matter, choosing to take this issue first, and having revoked the patent closed the proceedings and made no decision on morality. The basis for the decision: the disclaimer allowed by the German Court was held to constitute added matter by the EPO and disallowed (on essentially the same claim language and facts).

What a shame. What an opportunity missed. And what can we do about it?

Getting All Issues Heard at First Instance At The EPO

BOX 1

Getting Everything Decided At First Instance At The EPO

The EPO Brüstle Decision was decided on added matter. Having revoked the patent for contravention of Article 100(c) EPC, the EPO’s job was done. After all, only one ground is needed to revoke a patent. That is understood. There was no reason to continue the proceedings and deal with morality under Article 100(a) EPC or with sufficiency under Article 100(b) EPC. It may even be said that it would be incorrect to continue once the patent is revoked.c The EPO Brüstle case has now been punted into the long grass of the appeal system, and a successful appeal may well deal solely with the added matter issue, bouncing the case to the Opposition Division some 4(?) years later, at which time no doubt a sufficiency issue could be taken first, again potentially disposing of the case (in accordance with the EPC we should stress) and with no need yet to address morality – the one aspect of the case the outside world is interested in.

As practitioners, we would welcome a procedure that ensures all issues are addressed at e.g. the first opposition hearing. If added matter attacks fail but the patent is revoked for insufficiency then the hearing should nevertheless move onto novelty and inventive step, giving a decision under each of 100 (a), (b) and (c).

The EPO is invited to consider internal changes in opposition procedures so as to require a decision under each ground raised, so potentially under each of Article 100(a), (b) and (c) EPC.

While we do not have all the details of the system, it is widely understood that the EPO operates performance monitoring of Examiners – see Box 1. A revision and a procedural change may promote hearing of all issues at first instance – which would have meant morality being dealt with in the Brüstle EPO decision.

Current EPO Practice Re Morally Acceptable Starting Material

As of today, inventions in this field post 10 January 2008 are regarded as unproblematic, as morally acceptable starting material is available from at least that date. See Box 2 for details and an analysis of how that issue too needs reconsideration.

What Next? Back To The Intention Of The Legislator

The existing decision made by the EPO in WARF, as supplemented by the CJEU decision in C-34/10, enunciates a patentability test that does not enable the EPO adequately to deal with patent applications in which the fact situation presented differs from those in the WARF case, namely the proposed destruction of embryos by the person making the invention and by any person subsequently carrying out the invention.

The EPO Brüstle decision could have revised the test to deal with other fact situations; it didn’t, so we will have to do this ourselves.

The original object and purpose of the legislators in framing the wording of the exclusion from patentability in Rule 28(c) must be properly incorporated into the interpretation of the exclusion; and this must also be done taking into account the context in which human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), human induced pluripotent stem cells (hIPSCs) or other such cells are used and proposed to be used in each invention under examination.

When this approach is taken it is seen that the EPO practice that has developed in light of the WARF decision is too restrictive; patent protection is being denied for inventions the legislator did not intend to exclude from patentability.

Just as EPO disclaimer practice aims at disclaiming no more and no less than is necessary to achieve the object of the disclaimer, EPO practice on exclusions from patentability should aim at removing no more subject matter than is necessary to fulfil the legislator’s original object and purpose in framing the exclusion from patentability.

That object and purpose was to prevent commercialisation of embryos. Hence, EPO practice in this area should aim only at removing subject matter from a patent claim (and possibly also corresponding subject matter from elsewhere in the specification) that relates to commercialisation of embryos.

Interpretation of International Treaties

In G1/07 (Method by Surgery/Medi-Physics) and G2/08 (Dosage Regime/Abott Respiratory) the EBA indicated that all EPC provisions should be interpreted in accordance with Articles 31 and 32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969.

- Article 31 indicates that: “A treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose”

- Article 32 allows recourse: “…to supplementary means of interpretation, including the preparatory work of the treaty and the circumstances of its conclusion, in order to confirm the meaning resulting from the application of article 31”

Hence, to reach the correct interpretation we should look back in detail at the object and purpose of the exclusion as in the minds of those drafting the original legislation.

Legislative History Of The Biotechnology Directive

The first (1995) and second (1996) drafts of the Directive did not contain any exclusion provisions relating to the use of human embryos. The Group of Advisers to the European Commission on the Ethical Implications of Biotechnology issued its 8th Opinion in September 1996. Opinion No. 8 was concerned with ethical aspects of patenting inventions involving elements of human origin; an invention which “infringes the rights of the person and the respect of human dignity” cannot be patented.

In the third draft of the Directive submitted by the Commission in 1997, Article 6 read:

- Inventions shall be considered unpatentable where their commercial exploitation would be contrary to public policy or morality; however, exploitation shall not be deemed contrary merely because it is prohibited by law or regulation.

- On the basis of paragraph 1, the following shall be considered unpatentable:

(a) …

(b) …

(c) methods in which human embryos are used;

(d) …

Finally in the Common Position EC No 19/98 adopted by the Council on 26 February 1998, the text of Article 6(2)c was amended to read “uses of human embryos for industrial or commercial purposes”. This is also the text of Article 6(2)(c) of the final version of the Directive that was adopted on 6 July 1998.

It is seen that the original wording would have excluded “methods in which human embryos are used” and that the revised wording switched this order around and changed it slightly to result in the final wording “uses of human embryos for industrial or commercial purposes”. Perhaps the intention was to cover not only methods in which human embryos are used but also the products of methods in which human embryos are used.

‘Object And Purpose’ Of The Exclusion Under Rule 28(c)

In WARF it was concluded that the purpose of Rule 28(c) is “to protect human dignity and prevent the commercialization of embryos”.

Re commercialisation of embryos, the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, Article 3(2) states “In the fields of medicine and biology, the following must be respected in particular:… – the prohibition on making the human body and its parts as such a source of financial gain”.

In relation to the intention of the legislator to prevent commercialisation of embryos, it is relevant to examine in detail the way in fact in which, for example, hESC lines are prepared. It can then be seen whether there has been any commercialisation of embryos in connection with these technologies.

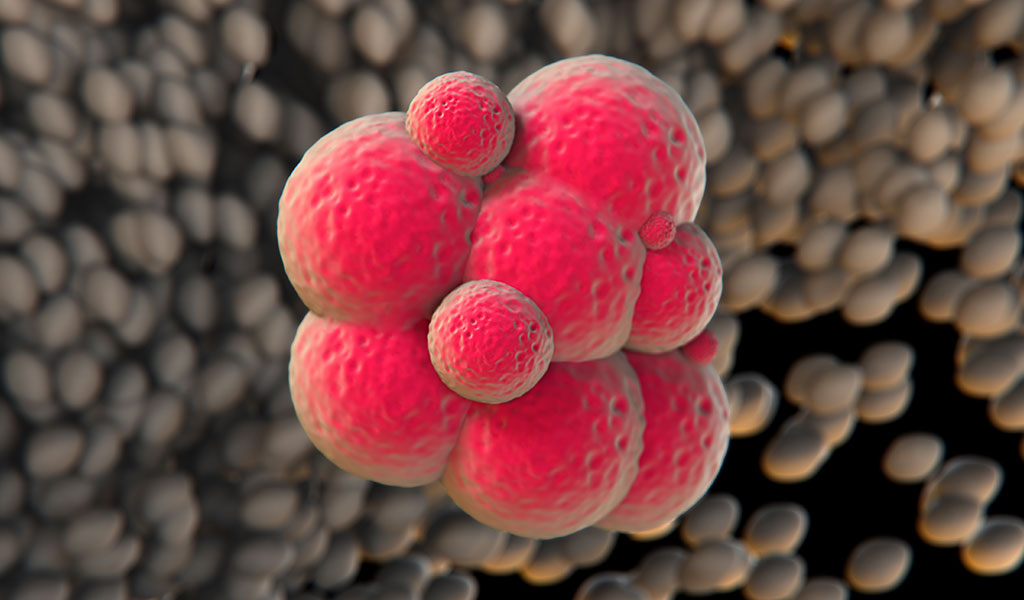

hESC Lines

With reference to the UK National Stem Cell Bank, European Human Embryonic Stem Cell Registry and the International Stem Cell Registry, one does not have to look far to see that hESC lines are derived from spare IVF embryos donated for research purposes.

Our first two examples are the MEL-1 and MEL-2 hESC lines which are derived from :

- “donated frozen IVF embryos no longer required for infertility treatment”.

Our next examples are the BJNhem19 and BJNhem20 hESC lines which are derived from:

- “the inner cell mass (ICM) of grade III poor quality blastocysts that were not suitable for in vitro fertility treatment”.

Lastly, we turn to the KCL002-WT4 hESC line which is derived from a:

- “supernumerary IVF embryo”.

The conclusions from the above are abundantly clear: in deriving and then using hESCs from these deposited hESC lines there is no commercialisation of embryos. Embryos used to derive the cell lines exemplified above have been donated and are described as “spare” or “supernumerary”.

Interpretation Of The Biotechnology Directive

In interpreting the wording of the Biotechnology Directive, we should also acknowledge those things that the legislator did not intend to do. In particular, we believe it must be accepted that the intention of the legislator was not to render morally unacceptable practices that were at the time routine, public, publicly available and practiced throughout many and possibly even all of the states of the European Community.

We refer, by way of example, to methods of in vitro fertilisation (IVF), which by the mid 1990s were an accepted medical practice throughout Europe and throughout the developed world.

The first “test tube” baby was born in the UK on 25 July 1978. According to figures from the UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (“HFEA”), in 1991 approximately 30,000 embryos were used in IVF methods in the UK alone. By 1997 the number of embryos used had risen to approximately 160,000 and by 2006 the number had risen to approximately 230,000.

The HFEA figures also indicate the number of embryos discarded and the number of embryos donated for research. To emphasise, these latter embryos are stated to be donated.

For convenience in understanding the relevant numbers, Fig. 1 below is a graphical representation of the number of embryos used, discarded and donated over a 15-year period from 1991 to 2006.

Note the significant increase in the number of embryos used (as IVF procedures become more common). Also note the significant increase in the number of embryos discarded – this clearly shows that ‘spare’ embryos from morally acceptable IVF methods are routinely destroyed.

If the spare embryos from morally acceptable IVF methods are routinely destroyed, how can subsequent medical use of those be rendered unacceptable by the Biotech Directive? How can research use for the good of human health be worse than destroying them?

Again, the intention of the legislator cannot have been to render IVF methods morally unacceptable – it is evident that IVF is indeed regarded as morally acceptable and part of this morally accepted procedure includes the routine destruction of embryos.

It can also not have been the intention of the legislator to render morally unacceptable contraceptive products and devices that destroy the embryo, for example, the “morning after pill” and intrauterine devices that prevent implantation. We acknowledge that some individuals and organizations find these products morally unacceptable, but the point is Europe as a whole does not.

The Correct Test

One phrasing of the modified WARF test (or part of the test) quoted from the CJEU Decision in Brüstle v. Greenpeace e.V. (C-34/10) is:

- ‘an invention must be regarded as unpatentable, even if the claims of the patent do not concern the use of human embryos, where the implementation of the invention requires the destruction of human embryos or their use as base material whatever the stage at which that takes place’

Under this modified WARF test, the WARF patent is revoked. So too are patents directed at contraceptives and IVF (in which embryo destruction is inevitable, as not all IVF embryos are used). The test is wrong.

We must go back to the intention of the legislator and reformulate the test to examine instead whether the invention relates to commercialisation of embryos. Inventions based on hESC lines, derived from donated, “spare” or “supernumerary” (to use the language of the IVF practitioners) embryos pass that test and should be patentable. We trust the EPO, perhaps through its Technical Board of Appeal, will eventually instate the test the legislator intended. The sooner the better.

BOX 2

The Search For Morally Allowable Starting Material – When Is An Embryo Not An Embryo?

The test for excluded subject matter under Rule 28(c) is explained in the current EPO Guidelines For Examination, Part G, Chapter II as follows:

- A claim directed to a product, which at the filing date of the application could be exclusively obtained by a method which necessarily involved the destruction of human embryos from which the said product is derived is excluded from patentability under Rule 28(c), even if said method is not part of the claim (see G 2/06). The point in time at which such destruction takes place is irrelevant.

This test prompts a search for the first date on which human embryonic stem cell lines can be derived without destroying an embryo, and there is an official date. The EPO accepts that as of 10th January 2008 such allowable starting material was available (Chung et al, Cell Stem Cell. 2008 Feb 7;2(2):113-7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.013. Epub 2008 Jan 10). An earlier publication by the same group (Klimanskaya et al, Nature. 2006 Nov 23;444(7118):481-5. Epub 2006 Aug 23) has not been accepted to date by the EPO as providing morally acceptable starting material, as the cells obtained were co-cultured with (and hence contaminated by) human embryonic stem cells obtained using conventional techniques considered to require embryo destruction.

The German Brüstle Decision raises another option: that embryos whose development has arrested are no longer embryos, with the consequence that human embryonic stem cell lines derived from those structures are not derived from embryos, in which case there can be no embryo destruction in the process.

In International Stem Cell Corporation v Comptroller General of Patents, [2013] EWHC 807 (Ch), a similar point was raised and Henry Carr QC gave the preliminary view:

- I agree with ISCC that if the process of development is incapable of leading to a human being, as the Hearing Officer has found to be the case in relation to parthenotes, then it should not be excluded from patentability as a ‘human embryo’.

This is in line with the decision in the German Federal Court; a structure that can not complete development into a human being is not an embryo. How does this help with the first date on which morally acceptable subject matter was available? Answer: stem cell lines exist and are deposited so as to render them publicly available in which the cells are derived from these non-embryo structures, and earlier than 10 January 2008.

Zhang et al, “Derivation of human embryonic stem cells from developing and arrested embryos”, Stem Cells 2006 Dec 24(12): 2669-76. Epub 2006 Sep 21 is one such disclosure of deriving human embryonic stem cells lines from these non-embryos, taking the date to 21 September 2006. There are many cell lines made in a similar manner from e.g. embryos rejected from in vitro fertilization procedures. We haven’t had the time yet to identify earlier examples, but we expect these go back earlier still.

Lastly, the CJEU in C-34/10 (the “Brüstle CJEU decision”) decided that totipotent cells are unpatentable and constitute embryos. The Chung et al techniques mentioned above remove a cell from an 8-cell blastomere, yielding a 7-cell structure that is an embryo and can complete its development and a 1-cell structure, used to derive a cell line. What is the potency of that 1-cell?

Van de Velde et al, Oxford Journals, Medicine, Human Reproduction, Volume 23, Issue 8, pp. 1742-1747 report that cells from the human 4-cell blastomere are totipotent. Does this mean that individual cells isolated from the 8-cell blastomere are also, or partially totipotent? If so, is that 1-cell structure also an embryo (the Chung technique splits one embryo into two embryos?) and is an embryo destroyed when the cell line is made from this 1-cell structure?