C364/13

In case C-364/13 the CJEU have decided that human parthenotes are not “human embryos” because they are incapable of commencing the process of development into a human being. Therefore parthenotes are a legitimate source of human embryonic stem cells for use in patentable technologies, with the consequence that such human embryonic stem cells were available from morally acceptable sources from November 2005 onwards. Furthermore, the Justices’ reasoning might be extended to other even earlier used techniques that may now be considered sources of human embryonic stem cells that are not excluded from patentability.

Background

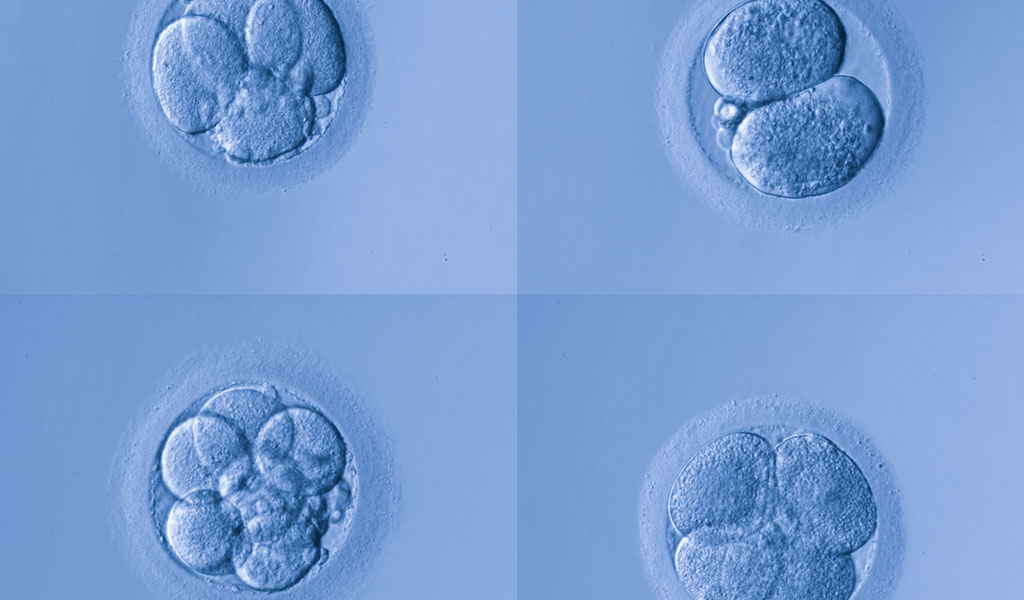

Following C-34/10, any non-fertilised human ovum for which division and further development are stimulated by parthenogenesis was to be considered a “human embryo”. Such a non-fertilised and stimulated human ovum is called a parthenote.

The CJEU’s ruling in C-364/13 followed a question referred from the UK High Court [[4]] to resolve whether stem cells derived from parthenotes that are incapable of developing into a human being are “human embryos” within the meaning of the Biotech Directive.-

This ruling was sought, and is important, because it narrows the definition of “human embryo” within the meaning of the Biotech Directive and broadens the range of acceptable inventions using stem cells from sources that are not excluded from patentability.

C-364/13 follows the preliminary opinion of Advocate General Cruz Villalón in this case [[3]] and is summarised in paragraph 39 of the decision, which states:

[The Biotech Directive] must be interpreted as meaning that an unfertilised human ovum whose division and further development have been stimulated by parthenogenesis does not constitute a ‘human embryo’ […], if […] it does not, in itself, have the inherent capacity of developing into a human being, this being a matter for the national court to determine.

A Parthenote Cannot Develop Into a Human

A parthenote cannot develop into a human. This is because it is essential for viability that half the chromosome complement of a human comes from an egg and half from a sperm cell. It is often said that the information encoded in the DNA that is held within every nucleated cell of a human being contains the total information required to build that particular human being. However, this is not so.

The DNA of the egg and the fertilising sperm are marked with further information as to their origin: egg or sperm. The DNA of each gamete is specifically imprinted, i.e. labelled, by a pattern of modifications to the DNA such that the activity of a large number of genes is defined by whether they come from the egg or the sperm. This information – this additional layer of genetic control – is essential for human development. In its absence, that is, in a parthenote where the whole genetic complement is derived from the egg, a human cannot result because an “embryo” lacking this imprinted information can never be viable.

This is the crux of the dispute considered by the CJEU in C-364/13. Whereas C-34/10 defined a biological scenario and excluded it from patentability, as noted above, the biological scenario is impossible. International Stem Cell Corporation (ISCC), applicant at the UK IPO attempted to patent an invention that relies on cells derived from parthenotes that were initially held to fall within the limits of the exclusion. Their patent was refused by the UK IPO and consequently they began legal proceedings to challenge this particular aspect of the interpretation of the exclusion.

The result is that C-364/13 modifies C-34/10 to recognise circumstances when a “fertilised human ovum” is not capable of commencing the process of development of a human being, such as for a parthenote, and is therefore not an embryo. Consequently, inventions utilising cells derived from such cells can be components of patentable inventions.

Date of Availability of Human Embryonic Stem Cells from Acceptable Sources.

We previously anticipated the likely impact of the CJEU decision following the Advocate General’s preliminary opinion in our article in the CIPA Journal [[5]]. To précis our observations set out in this article: in our opinion the reasoning to be used in C-364/13 will mean that parthenotes are not the only source of “morally acceptable” pluripotent stem cells and consequently a source of stem cells available for use in patentable inventions was disclosed by Mina Alikani in November 2005 [[5]].

Human embryonic stem cells are derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) of human blastocysts; a blastocyst being a stage in human embryonic development. However, if a blastocyst is not “capable of commencing the process of development of a human being” then it is not a human embryo within the definition of the Biotech Directive. As noted above, parthenotes fall within this definition and therefore are an acceptable source of human embryonic stem cells, but so do other blastocysts.

In particular, there are other chromosome abnormalities that are seen in blastocysts which prevent their being capable of commencing the process of development of a human being. One such abnormality is that described by Alikani where the cells of a blastocyst carry three copies of a particular chromosome rather than the normal two. For most human chromosomes the presence of the additional gene copies carried on the additional chromosome mean the blastocyst is not viable. However, removal and culture of a human embryonic stem cell from the ICM of such a non-viable blastocyst can yield a cell which has auto-corrected its chromosome number. Following the reasoning set out in C-364/13 stem cells from such a source can be included in patentable inventions.

As noted in our previous article [[5]], this insight follows from the research of Dan Wise and Annabel Strawson of Carpmaels and Ransford LLP and we are grateful for their telling us about it.

A Still Earlier Date of Availability?

Given that a blastocyst with an aberrant chromosomal complement is unlikely to be “capable of commencing the process of development of a human being” we have also considered other chromosomal abnormalities and whether they provide, perhaps, other opportunities to push back the date of first availability of human embryonic stem cells from sources that are not human embryos within the definition of the Biotech Directive.

In this vein we note that stem cells derived from non-viable triploid zygotes were disclosed in September 2001. A zygote is a fertilised egg, i.e. a single cell containing male- and female-originating genetic information. The disclosures considered here are a conference abstract by Escribà et al. [[6]] and EP1516925A1 [[7]].

These publications describe triploid zygotes, i.e. single cells carrying three complete copies of the genome; as such they are not viable. Triploidy is normally seen as a result of an ovum being multiply fertilised by two sperm. Consequently such fertilised ova arguably fall outside the scope of the definition of “human embryo” given for C-34/10 (and quoted above) since in this case fertilisation is not such as to commence the process of development of a human being. In the case of a triploid blastocyst, no ICM forms and so embryonic development stops without the visible development of embryonic stem cells.

Furthermore, following the reasoning of C-364/13, such a fertilised, triploid ovum “does not, in itself, have the inherent capacity of developing into a human being”.

These papers [[6]] and [[7]] disclose a micro-surgical technique for removing the additional genetic information from the fertilised ovum. Use of this technique allows normal development to proceed – including development of a blastocyst with an ICM from which human embryonic stem cells can be obtained. Therefore, following the rulings discussed above, obtaining human embryonic stem cells from such non-viable nuclei would arguably be acceptable for patent protection in Europe.

Thus, on the face of it, stem cells from sources that are “morally acceptable” under the Biotech Directive have been available since September 2001. However, for completeness, this technique does not simply restore developmental potential. Potentially it can also restore viability to a triploid embryo. Indeed Kattera and Chen [[8]] report a live birth resulting from implantation of a blastocyst that developed in culture following use of a similar technique. In other words, this technique potentially recues totipotent cells, i.e. human embryos, from previously non-viable zygotes.

So, turning back to the decision handed down by the CJEU for C-364/13 we observe that this decision particularly applies to parthenotes and, in particular, parthenotes that have not been genetically modified [[1, para 35]] with the specific exclusion that they do not have in themselves “the inherent capacity of developing into a human being, this being a matter for the national court to determine.”

Thus extending the reasoning of C-364/13 to other human embryonic stem cells derived from other chromosomally aberrant, and therefore non-viable embryos, also extends this specific exclusion to these other stem cells. In the case of the stem cells described by Escribà et al. [[6]] and in EP1516925A1 [[7]], these are only possible by the application of a specific surgical technique. In this instance it is arguable that fertilised zygotes treated, indeed genetically modified, in this way did not originally have the “inherent capacity of developing into a human being” before being treated.

We note that one part of the Advocate General’s Opinion that was not taken up by the CJEU for inclusion in decision C-364/13 was that parthenotes should be excluded from patentability “as long as they are not capable of developing into a human being and have not been genetically manipulated to acquire such a capacity” [[3, para 80]]. The Advocate General was considering the case of viable embryos being rendered non-viable by genetic modification. In the case of the triploid zygotes considered above the opposite applies: genetic modification can confer viability.

Thus we need to look at the reverse scenario from that considered by the Advocate General: following the reasoning of decisions C-34/10 and C-364/13, can genetic modification of a non-viable embryo (i.e. not an embryo within the Biotech Directive) produce human embryonic stem cells that are acceptable for use as a component of a patentable invention? Is the capacity of a triploid zygote to be corrected by outside intervention sufficient to be considered as having “the inherent capacity of developing into a human being?”

As noted above, the ruling in C-364/13 is clear that judging whether an embryo has the inherent capacity of developing into a human being is a matter for the national courts [[1, para 39, final clause]]. Given the differing opinions expressed in Amicus briefs from various member states during consideration of C-364/13, we expect that the CJEU may have to revisit this matter again in due course. Until then there appears to be arguable basis that a source of human embryonic stem cells that are acceptable within the provisions of the Biotech Directive has been available since September 2001.

Conclusion

No decision has yet been issued by the President of the EPO as to how, or whether, C-364/13 will be applied to EPO practice.

However, following previous decisions by the CJEU relating to the subject of patentability of human stem cells, the EPO has amended its practice promptly in light of the CJEU’s ruling; we expect that this will also be the case for this decision.

Therefore, we consider that stem cell patents dating from November 2005 will not comprise subject matter excluded from patentability. This is a major step forward for the patentability and ongoing defence of these early-days stem cell patents.

Finally, we note that there is arguable basis that that stem cell patents dating from September 2001 will not comprise subject matter excluded from patentability. However, deciding whether stem cells derived from triploid zygotes are patentable subject matter will likely require more legal proceedings before, at least, EU national courts. Someone will have to decide when a triploid embryo has the inherent capacity of developing into a human being.

References

- CJEU Decision C-364/13

- CJEU Decision C-34/10

- C-364/13 Preliminary Opinion of Advocate General Cruz Villalón

- UK High Court Decision, re International Stem Cells Corporation versus Comptroller (Appeal Ref. CH/2012/0488)

- CIPA Journal, September 2014, pp505–507

- M. J. Escribà et al., September 2001, Fertility and Sterility, Volume 76, Issue 3, Supplement 1, Page S238

- EP1516925A1

- Kattera and Chen, 2003, Human Reproduction, Vol.18, No. 6 pp. 1319–1322