Lidl v Tesco [2023] EWHC 873 (Ch)

In its recent decision [2023] EWHC 873 (Ch), the High Court held that Tesco had infringed Lidl’s registered trade mark rights, as well as their rights in passing off and copyright, all in respect of the well-known blue and yellow Lidl logo. However, the decision wasn’t all positive for Lidl since the court ruled in favour of Tesco on their counterclaim that Lidl’s wordless mark had been registered in bad faith.

Background

Lidl have been operating in the UK since 1973, during which they have always used the familiar blue and yellow Lidl logo. Last year Lidl accused Tesco of infringement of their registered trade mark rights in relation to two versions of this logo: the well-known “Mark with Text” as well as a version without the text, referred to herein as “the Wordless Mark”. Lidl also accused Tesco of passing off and copyright infringement.

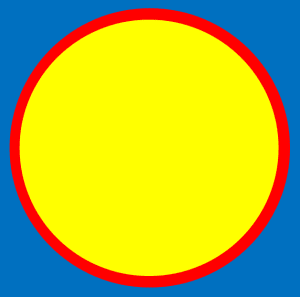

Lidl’s claim concerns the Tesco Clubcard Prices Promotion logo, referred to herein as the “CPP Sign”, which consists of a yellow circle overlapped onto a blue square background. Tesco’s Clubcard scheme launched in 1995 but it wasn’t until September 2020 that they launched the discrete advertising strategy which uses the CPP Sign.

- Lidl’s Logo

- Lidl’s Wordless Mark

- Tesco’s CPP Sign

Lidl’s complaint specifically relates to the blue background with the yellow circle overlaid, this being the common element between the logos. In summary, Lidl alleged that Tesco deliberately copied this graphic with the intention of confusing customers and deceiving them into believing that Tesco Clubcard prices are equivalent to Lidl’s prices. Lidl also claimed that Tesco’s aim in using the CPP sign was to improve their ability to compete with discounter supermarkets and take advantage of Lidl’s reputation of good value for money.

Tesco pursued a counterclaim alleging that Lidl’s registered trade mark rights in respect of the Wordless Mark should either be declared invalid on the grounds that they were registered in bad faith or revoked for non-use and lack of distinctive character.

Infringement of Trade Mark Rights

The court unsurprisingly acknowledged that the Mark with Text has a reputation in the UK, however the question of reputation in relation to the Wordless Mark was less clear cut and thus the court would consider the two marks separately.

With regards to the Mark with Text, the CPP mark was considered similar enough to form an overall impression of similarity in the mind of the average consumer, resulting in two types of confusion: confusion of origin and confusion of price comparison. Accordingly, the court found that Lidl had established the necessary link between the marks.

It was further decided that Tesco had caused detriment to the distinctive character of the Lidl Mark with Text and that Tesco’s use of the CPP Sign caused a “subtle but insidious transfer of image”; this second point being somewhat controversial in view of the court’s earlier acknowledgment that Tesco did not have any intent to cause detriment. Nevertheless, it was decided that the CPP sign infringes Lidl’s trade mark rights in relation to the Mark with Text.

The court then touched briefly on the Wordless Mark, concluding that their position with respect to infringement was the same as that of the Mark with Text and noting that further analysis of the Wordless Mark would be irrelevant since the Wordless Mark has never been used in the UK and therefore any reputation it may have acquired is derived solely from use as a background in the Mark with Text.

Passing Off

Unsurprisingly, in view of the decision on trade mark infringement, the court found that Lidl had suffered damage as a result of Tesco’s misrepresentation.

Tesco’s defence against Lidl’s claim to passing off rested on the proposition that even if customers were deceived into believing Tesco Clubcard prices were equivalent to Lidl prices, Lidl has no evidence to suggest that this is in any way untrue. However, the court sided with Lidl in finding that customers would be discouraged to check the prices of corresponding Lidl products, consequentially improving Tesco’s value perception as a result of a misleading association with the Lidl Brand.

Copyright Infringement

Briefly, on the subject of copyright, the court were satisfied firstly that copyright subsists in the Mark with Text, secondly that the Mark with Text is owned by Lidl and finally that Tesco copied a substantial part of the Mark with Text. Thus, the judgement was made that Lidl’s copyright is also infringed.

Tesco’s Counterclaim

Tesco’s counterclaim challenged the validity of the Wordless Mark, on three different grounds: non-use, lack of distinctive character and registration in bad faith.

Although Lidl admitted their Wordless Mark has only ever been used in the UK, with the expectation of use as the background of the Mark with Text, they were still able to establish that the Wordless Mark is perceived by the public as being relevant to the Lidl brand. Therefore, Tesco’s counterclaim that the Wordless Mark should be revoked on the grounds of non-use and lack of distinctive character was refused.

However, the court did side with Tesco in concluding that the Wordless Mark was registered with the sole intention of securing a broader monopoly and without any intention of using the Wordless Mark as anything over than a background for the Mark with Text. Thus, the court decided that Lidl’s trade mark rights in respect of the Wordless Mark are invalid on the grounds of bad faith, though it should be noted that, in view of the decision on infringement relating to the Mark with Text, this finding does not advance Tesco’s position in any way.

Discussion

This, perhaps unexpected, decision illustrates the value and strength that reputation can afford to UK trade marks, indicating that reputation and goodwill may even have the potential to broaden the scope of protection attained by a registered trade mark.

We are also reminded about the power of the, often undervalued, protection provided by unregistered rights such as copyright and passing off. While the decision on trademark infringement is somewhat unexpected in view of the court’s finding that Tesco had no intent to cause damage, the decision on copyright infringement is potentially even more surprising, since we would likely not have anticipated that such a simple brand logo would qualify as an artistic work suitable for copyright protection.