AMERICAN AXLE & MANUFACTURING, INC. V. NEAPCO HOLDINGS LLC (FED. CIR. 2019)

The United States Patent and Trade Mark Office (USPTO) regularly raises objections under §101 USC 35 that inventions aren’t patentable because they are directed to a law of nature. These are a well-known and regular frustration for practitioners in the life sciences, for example. In contrast, they are, as one might expect, a significantly smaller problem for the mechanical arts. However, that is the logic underlying a recent US Federal Circuit decision.

American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. v. Neapco Holdings LLC (Fed. Cir. 2019) relates to a method of manufacturing that the Federal Circuit has found to be non-patent eligible because the novel technical feature of claim 1 was held to be directed to a law of nature. In this case, the laws of nature invoked are the broad physical principles associated with vibrational frequency and dampening of vibrations.

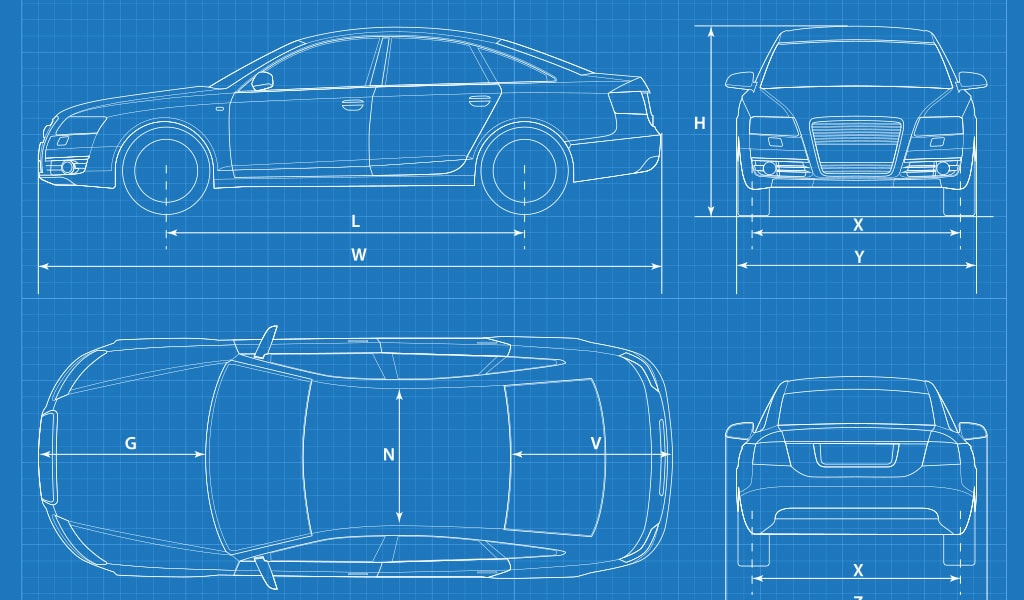

The Invention

The invention in this case relates to drive shafts in automobiles (U.S. Patent 7,774,911; “‘911 patent”). Vibration in drive shafts is a known problem and methods have been devised to address this. Such methods include using drive shaft liners, i.e. hollow tubes made of a fibrous material such as cardboard, which also have the advantage of being of relatively low cost. Prior to the ‘911 patent it was only known to use liners in draft shafts to attenuate a single type of vibration – “shell mode” vibration. However there is another type of vibration – “bending mode” and it was not previously known that liners could attenuate both bending and shell mode vibration.

Indeed, the patent at issue solved these problems by disclosing that liners could be “tuned” to control bending mode vibrations or the combination of bending and shell mode vibrations. This solution is given in claim 1 of the ‘911 patent.

- A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising:

providing a hollow shaft member;

tuning at least one liner to attenuate at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member; and

positioning the at least one liner within the shaft member such that the at least one liner is configured to damp shell mode vibrations in the shaft member by an amount that is greater than or equal to about 2%, and the at least one liner is also configured to damp bending mode vibrations in the shaft member, the at least one liner being tuned to within about ±20% of a bending mode natural frequency of the shaft assembly as installed in the driveline system.

Claim Scope

However, the language of claim 1 defines invention in terms of an object to be achieved whereby it recites “tuning at least one liner to attenuate at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member”. Thus the skilled person is presented with a number of features of a shaft assembly of a driveline system and then told to, simply, “tune” the liner of a drive shaft assembly to prevent vibration. There is no definition in the claims of a method of tuning and so the claim simply discloses to the skilled person that it is possible to solve the problem and leaves them to find the precise solution.

If the skilled person is told that there is a problem and a solution exists and they should find it then, the skilled person not being at all inventive, must find a solution to the problem without inventive effort. Further, if there is a specific solution disclosed in the specification then this must be obvious as having been achieved without inventive effort.

Therefore, in the absence of further claim features relating to the tuning the Federal Circuit found that the skilled person had effectively just been told to apply known physical laws to the tuning of the liner even though the art had not hitherto recognised that it is possible to attenuate the “at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member” by means of altering the liner.

So, while the patentees recognised and defined the problem, and disclosed a working solution, the scope of their claims was not consistent with defining their particular solution. In the absence of such a definition the skilled person only had their non-inventive skill and the common general knowledge to rely on and thus the Federal Circuit found that the scope of claim 1 implicitly comprises obvious subject matter.

Contrast with European “Problem” Inventions.

While the section 101 rejection appears frustrating and concerning to practitioners, we might take the view that the revocation of the claims is due to their over-broad nature and that a narrower claim directed to novel and inventive technical teaching might have been allowable. But would a similar situation have existed in other jurisdictions? For instance, in Europe before the European Patent Office (EPO)?

European practice allows novelty and inventive step to be recognised for so-called “problem inventions”. That is, inventions where once it is realised that there is a problem the solution to that problem is obvious. Accordingly, the inventive step is in recognising a hitherto unappreciated technical problem.

The problem of bending mode vibration in the drive shaft liners would appear to be such a problem invention. Thus the inventive step under European practice might be argued to be in the realisation that bending mode vibrations were a problem that could be solved by adaptation of the drive shaft liner.

Accordingly, it appears arguable that the broad formulation of the claim that was rejected in America might have been allowable in Europe because of this difference in practice for claiming such subject matters.

One again, the difference in scope of protection available to inventors in various jurisdictions arises for disparate reasons and has far reaching affects. In this case, a claim that is considered overbroad and therefore revoked in the US would appear to be technically reasonable and arguably allowable under European practice. This leads to a situation whereby a European and US practitioners should be cautious regarding the scope of the claims in the US for such inventions and, perhaps, more bullish about the scope of protection available at the EPO.

Share this article

Our news articles are for general information only. They should not be considered specific legal advice, which is available on request.